Pelvic floor dysfunction includes a group of disorders causing abnormalities of bowel storage and bowel emptying, as well as pelvic pain. This information is intended to help patients gain a better understanding of the disorders making up pelvic floor dysfunction, as well as the evaluation and treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction. It is intended to help patients who suspect that they may have pelvic floor dysfunction better understand the reason for their symptoms, and help them realize that with proper evaluation and treatment it is possible to get relief from symptoms that can be quite disabling. Patients should know that a thorough, step-wise approach to evaluate their symptoms may offer prompt diagnosis and treatment for what often is a long-standing, frustrating problem.

Pelvic floor dysfunction can be caused by a number of specific conditions. These include:

- Rectocele

- Paradoxical Puborectalis Contraction

- Pelvic pain syndromes:

- Levator Syndrome

- Coccygodynia

- Proctalgia Fugax

- Pudendal Neuralgia

WHAT IS THE PELVIC FLOOR?

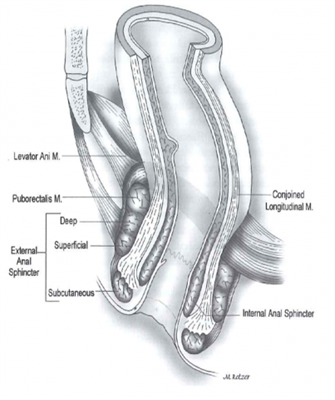

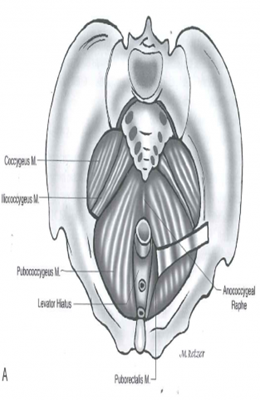

The pelvic floor is a sheet of muscle through which the rectum passes and becomes the anal canal. The anal canal is surrounded by the anal sphincter complex, which is comprised of both an internal and external component. Many of the disorders above are due to improper functioning of the pelvic floor muscles. The levator ani muscle (also called the pelvic diaphragm) is the major component of the pelvic floor. The levator ani muscle is actually a pair of symmetrical muscular sheets comprised of 3 individual muscles – the iliococygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis. The puborectalis is a U-shaped muscle that attaches to the pubic tubercle (“the pubic bone”) and wraps around the rectum – under normal circumstance, this muscle is contracted, maintaining a “bend” in the rectum and contributing to stool continence. The act of bearing down to pass a bowel movement typically causes this muscle to relax, allowing the rectum to straighten. In addition to the rectum, the urethra, which carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body, also passes through the front portion of the pelvic floor, as does the vagina in females.

Legend: This image shows a view of the pelvic floor muscles from above. The image on the right shows the relationship of the rectum as it passes through the pelvic floor and becomes the anus, surrounded by the anal sphincter complex.

ASCRS Textbook 2nd edition, pages 11 and 3.

HOW IS PELVIC FLOOR DYSFUNCTION EVALUATED?

As many components of evaluation are quite similar in pelvic floor dysfunction, we’ll discuss the methods used to evaluate these disorders prior to discussing each disorder separately. The most important part of evaluating a patient with suspected pelvic floor dysfunction is a thorough medical history and physical examination, including an examination of the pelvic floor. An important aspect of the history includes a thorough obstetrical (child-bearing) history in women. This should seek to identify a history of difficult deliveries, forceps deliveries, prolonged labor, and traumatic tears or episiotomies (controlled surgical incision between the rectum and vagina to prevent traumatic tearing during childbirth). A thorough history of the patient’s bowel patterns, including diarrhea, constipation, or both, is also essential. Other key parts of the history include prior anorectal surgeries and the presence of absence of pain prior to, during, or following a bowel movement.

After a complete history and physical examination, a number of tests may be performed, depending on the patient’s symptoms and the physician’s suspicion of what may be causing the symptoms. These tests can sometimes be uncomfortable or somewhat embarrassing for the patient, but can provide valuable information to help determine what is causing the patient’s symptoms and help provide some relief.

ENDOANAL/ENDORECTAL ULTRASOUND:

This test uses sound waves to create anatomic pictures of the anus and its surrounding sphincter muscles and the wall of the rectum. It typically involves the insertion of a slender ultrasound probe that is generally no bigger in diameter than an index finger into the anus and/or rectum. You are usually asked to perform an enema prior to the procedure to empty the anus and rectum. Sedation is generally not given. The procedure usually takes just a few minutes and is generally associated with only minor discomfort.

ANORECTAL MANOMETRY TESTING:

This test provides the physician with information regarding how well the anal sphincter muscles squeeze at rest and with voluntary attempts to squeeze the muscle. It also helps determine how effective the sensation of the anus and rectum is. The compliance (distensibility) of the rectal wall can be determined. The sensation and compliance results can provide important information explaining how the rectum responds to stool entering the rectum (either over- or under-reactive to the presence of the stool). Finally, information about the function of reflexes in the anus and rectum necessary to pass stool can be determined. The test involves placing a small flexible catheter (about the diameter of a pencil) with a small balloon on the end into the rectum. Similar to the ultrasound test, which is often done at the same setting, no prep is required other than an enema, and the patient is awake during the procedure because he/she must be able to follow commands or indicate when they feel certain sensations.

PRUDENDAL NERVE MOTOR LATENCY TESTING:

This test evaluates the function of the nerves to the pelvic floor and anal sphincters. It involves stimulation of the pudendal nerve from inside the anus using an electrode on the end of the examiner’s finger. Stimulation of the nerves causes muscle contraction, which can sometimes be mildly uncomfortable for the patient, and conduction through the nerve is measured to determine whether the nerve is conducting signals to the muscles at a normal rate or if it is delayed.

ELECTROMYOGRAPHY (EMG):

EMG is another means of evaluating the activity of the nerves and muscles of the anal sphincter and pelvic floor. There are a number of different ways to perform this test - some involve the placement of small needles into the muscles while others utilize a plug that is placed into the anal canal. It can be a little more uncomfortable for the patient than some of the other tests that have been described, but patients should be reassured by the fact that it can provide valuable information in certain situations.

VIDEO DEFECOGRAPHY:

During this study, the patient is given an enema of thickened liquid (“contrast”) that can be seen on x-rays. A special type of x-ray machine then takes video pictures while the patient sits on a commode, recording the movement of the muscles of the pelvic floor as the patient evacuates the liquid from the rectum. As this study very realistically re-creates what happens during an actual bowel movement, it provides valuable information about the coordination of movement of the pelvic muscles that occurs during the process of a bowel movement. An alternative to the more traditional video defecography is dynamic MRI defecography, in which the images are captured with the use of an MRI rather than regular x-rays. This is a relatively new procedure that is performed only in selected centers.

During this study, the patient is given an enema of thickened liquid (“contrast”) that can be seen on x-rays. A special type of x-ray machine then takes video pictures while the patient sits on a commode, recording the movement of the muscles of the pelvic floor as the patient evacuates the liquid from the rectum. As this study very realistically re-creates what happens during an actual bowel movement, it provides valuable information about the coordination of movement of the pelvic muscles that occurs during the process of a bowel movement. An alternative to the more traditional video defecography is dynamic MRI defecography, in which the images are captured with the use of an MRI rather than regular x-rays. This is a relatively new procedure that is performed only in selected centers.

COLONIC TRANSIT STUDY:

This test, which is also sometimes called a Sitz marker study, is valuable in patients with severe constipation in helping to determine whether the cause of constipation is due to a problem with ineffective contraction of the colon or due to a problem with passage of stool through the pelvis. To perform this test, a small gelatin capsule containing small rings that will appear on an x-ray is swallowed.

Once swallowed, the capsule dissolves and the rings are released into the intestinal tract. X-rays of the abdomen are then taken at defined periods of time (for example, on days 1, 3, and 5 or on days 2 and 5) and the movement of the rings through the colon is tracked. Most of the rings should have passed out of the body in bowel movements by day 5. If not, the number and pattern/location of the remaining rings is noted on the x-ray. If the rings remain together at the beginning of the colon or scattered throughout the entire colon, it is thought to mean that there is a problem with overall colon motility. If the remaining rings are clustered near the end of the colon or rectum, it may mean that some sort of pelvic floor outlet obstruction may be causing the constipation.

BALLOON EXPULSION TEST:

This test involves the placement of a small rubber balloon into the rectum, which is then filled with water. The patient is then asked to sit on a commode or toilet and expel the balloon. Most patients should be able to expel the balloon in under a minute. Failure to do so may indicate some degree of obstructed defecation.

PELVIC FLOOR DYSFUNCTION: DISORDERS

RECTOCELE

WHAT IS A RECTOCELE?

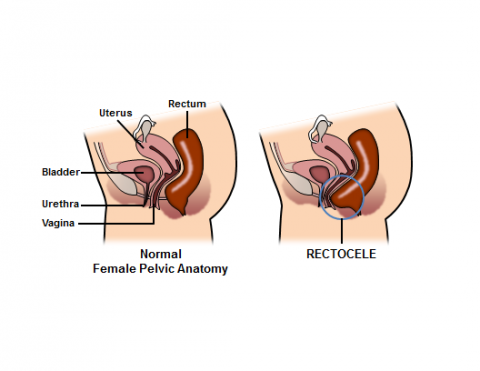

The vagina and the rectum can be thought of as two muscular tubes running parallel to each other and sharing a common muscular wall between them – the back wall of the vagina and the front wall of the rectum together make up what is called the “rectovaginal septum”. A rectocele occurs when the rectovaginal septum becomes weak and the rectum bulges forwards into the vagina.

Rectocele Diagram Courtesy of Robin Noel

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Department of Surgery

4th Floor Maloney Building, Fitts Education Center

Philadelphia, PA 19104

215-349-5043

www.uphs.upenn.edu/surgery/

www.uphs.upenn.edu/surgery/admin/noel.html

The finding of a small rectocele on examination is very common and is of no concern if the patient does not have significant symptoms. When a rectocele becomes large, stool can become trapped within it, making it difficult to have a bowel movement or creating a sensation of incomplete evacuation. Symptoms are usually due to stool trapping, difficulty passing stool, and protrusion of the back of the vagina through the vaginal opening. During bowel movements, women with large, symptomatic rectoceles may describe the need to put their fingers into their vagina and push back toward the rectum to allow the stool to pass (“splinting”). Rectoceles are more common in women who have delivered children vaginally.

HOW IS A RECTOCELE DIAGNOSED?

Often, a rectocele is easily recognized on physical examination at rest or with performance of various maneuvers. In instances of very large rectoceles, the back wall of the vagina may bulge out beyond the opening of the vagina. Smaller rectoceles may only be obvious when the woman strains. Video defecography can be useful in the diagnosis of a rectocele. In the presence of a rectocele, the contrast material can be seen bulging from the front of the rectum into the back of the vagina. Sometimes the contrast material stays in the rectocele while the liquid in the rectum is expelled — this is called “stasis”, or stool trapping.

HOW IS A RECTOCELE TREATED?

In the absence of severe symptoms, the recommended treatment for a rectocele is non-surgical, and focused on optimizing stool consistency to aid in the passage of stool. This often involves increasing fiber intake (which may also include taking a daily fiber supplement) and increasing fluid intake. Biofeedback, which is a special form of pelvic floor physical therapy aimed at improving a patient’s rectal sensation and pelvic floor muscle contraction, may also be helpful. As described above, the patient may insert one or two fingers into the vagina to splint the vagina during attempts to pass stool.

When symptoms persist despite appropriate non-surgical measures, surgical treatment may be considered. This usually involves reinforcement of the rectovaginal septum, using either an approach through the rectum (as favored by most colon and rectal surgeons) or through the vagina (as favored by most gynecologists). Some surgeons have recently begun utilizing a technique called the STARR (stapled transanal rectal resection) procedure, in which a surgical stapling device is used to remove a portion of the rectocele. This is a newer procedure that is not performed by all colon and rectal surgeons, and its success and complication rates are still being studied.

PARADOXICAL (NON-RELAXING) PUBORECTALIS SYNDROME:

WHAT IS PARADOXICAL (NON-RELAXING) PUBORECTALIS SYNDROME?

The puborectalis muscle is a muscular sling that wraps around the lower rectum as it passes through the pelvic floor. It serves an important role in helping to maintain fecal continence and also has an important function during the act of having a bowel movement. At “rest,” the puborectalis is contracted and pulls the rectum forward; creating a sharp angle in the rectum that helps to prevent passive leakage of stool. During the normal process of defecation, as one bears down to pass stool, the puborectalis reflexively relaxes and straightens out, allowing stool to pass more easily through the rectum into the anal canal. Paradoxical puborectalis syndrome occurs when the muscle does not relax when one bears down to pass stool. In some cases, it actually contracts harder, creating an even sharper angle in the rectum, resulting in difficulty emptying the rectum, a term sometimes referred to as obstructed defecation. Patients often complain of the sensation of “pushing against a closed door”. Often, there is a history of needing to use an enema to have a bowel movement. Generally, there is no associated rectal pain or discomfort, which helps distinguish it from other pelvic floor syndromes. The exact cause is unclear, but it is thought to be due to a combination of factors that may include improper functioning of the nerves and/or muscles of the pelvic floor. Psychological mechanisms may also play a role.

HOW IS PARADOXICAL (NON-RELAXING) PUBORECTALIS SYNDROME DIAGNOSED?

This condition is usually diagnosed by a combination of longstanding difficulty passing bowel movements along with various testing modalities, including manometry, EMG, and defecography. These would demonstrate the puborectalis muscle not relaxing during the act of having a bowel movement. Patients will often have an abnormal balloon expulsion test, as well.

HOW IS PARADOXICAL (NON-RELAXING) PUBORECTALIS SYNDROME TREATED?

The management of paradoxical (non-relaxing) puborectalis syndrome is largely non-surgical. The mainstay of treatment is biofeedback therapy. As patients perform this specialized form of pelvic floor physical therapy, they are often able to view EMG or manometry tracings produced by a sensor in the rectum so that they can actually visualize the results of their efforts to relax the pelvic floor. Portable units have even been developed for home use. The success rate of biofeedback for this condition ranges from 40-90%, and most failures are due to the patient not keeping up with their exercises or performing them incorrectly. The implantation of a sacral nerve stimulator to modulate the input from the nerves to the muscles of the pelvic floor has been shown to be effective in some instances, with success rates as high as 85% in carefully selected patients. For severe cases where these methods fail, surgical creation of a colostomy, through which the patient passes stool into a bag on the abdominal wall, may be a last option, though this is very rarely required.

PELVIC PAIN SYNDROMES

Chronic pelvic pain can be seen in up to 11% of men and 12% of women, and results in 10% of the total visits to gynecologists. There are a number of types of pelvic pain syndromes, which will be discussed further.

LEVATOR SYNDROME:

WHAT IS LEVATOR SYNDROME?

Patients with levator syndrome experience episodic pain, pressure, or discomfort in the rectum, sacrum (lowest part of the spine), or coccyx (tailbone) associated with pain in the gluteal region and thighs. The pain is often described as a vague, dull, or achy pressure sensation high in the rectum that may be worse with sitting or lying down. The pain comes and goes and may last for hours or days. The exact cause is not known, but anxiety and depression have been closely associated with levator syndrome.

HOW IS LEVATOR SYNDROME DIAGNOSED?

There is no test that will definitively confirm the diagnosis of levator syndrome. It is often considered a “diagnosis of exclusion,” meaning that care must be taken to rule out other causes of pain before making a diagnosis of levator syndrome. Patients often will experience similar discomfort during a digital rectal examination when the examiner’s finger places traction on the puborectalis muscle.

HOW IS LEVATOR SYNDROME TREATED?

A number of methods of treatment are available for levator syndrome. Physical therapy, including digital massage of the puborectalis with a combination of heat and muscle relaxants, has been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms in up to 90% of patients. Injection of local anesthetics and anti-inflammatory agents into the puborectalis muscle can provide relief, though the results are often inconsistent and short-lived. Electrical stimulation of the pelvic floor muscles using a probe in the rectum has also been used – although the results with this are extremely variable. Biofeedback therapy has been used with excellent results in terms of relieving discomfort. A newer modality that is being investigated is sacral nerve stimulation. This procedure, which is more commonly used to treat fecal and urinary incontinence, involves the placement of electrodes that stimulate the nerves to the pelvis.

COCCYGODYNIA:

WHAT IS COCCYGODYNIA?

Coccygodynia may often be part of a group of pelvic floor symptoms, but it is distinguished by distinct pain that is evoked with pressure or manipulation of the coccyx or tailbone. It is usually due to a history of trauma to the tailbone, but other causes include weakening of the tailbone due to poor blood flow (avascular necrosis) and referred pain from herniated lumbar disc.

HOW IS COCCYGODYNIA DIAGNOSED?

It usually is diagnosed by a combination of history and physical examination. X-rays should be done to rule out either a recent or longstanding fracture of the tailbone.

HOW IS COCCYGODYNIA TREATED?

Surgical excision of the tailbone (coccygectomy) was once popular, but now is rarely performed as the initial means of treatment. Injection of local anesthetics and anti-inflammatory agents with manipulation of tailbone under anesthesia can provide relief from pain in up to 85% of patients. Coccygectomy may be considered for those who fail injection therapy.

PROCTALGIO FUGAX:

WHAT IS PROCTALGIA FUGAX?

Proctalgia fugax is characterized by fleeting pain in the rectum that lasts for just a minute or two. Because the pain comes and goes quickly and unpredictably, it is difficult to evaluate. It is thought that it is probably due to spasm of the rectum and/or the muscles of the pelvic floor and often wakes patients from sleep.

HOW IS PROCTALGIA FUGAX DIAGNOSED?

Proctalgia fugax may be diagnosed after a careful history and examination and thorough evaluation have been performed to rule out more serious causes of rectal pain.

HOW IS PROCTALGIA FUGAX TREATED?

Muscle relaxants may provide some relief from the intermittent discomfort associated with proctalgia fugax. The patient should be otherwise reassured that the symptoms are not a sign of another more serious disorder.

PUDENDAL NEURALGIA:

WHAT IS PUDENDAL NEURALGIA?

Pudendal neuralgia is characterized by chronic pain in pelvis and/or the perineum in the distribution of the pudendal nerves, which are the main sensory nerves of the pelvis. It may present as pain in the vulva, testicles, rectum, or prostate. It may also cause problems with defecation. Usually it is due to entrapment of the nerve(s) by pelvic muscles and sometimes is made better or worse by changes in position. It may occur after pelvic trauma and is also common in those with chronic, repetitive trauma to the perineum, such as cyclers and rowers.

HOW IS PUDENDAL NEURALGIA DIAGNOSED?

Typically, pain may be exacerbated during digital rectal examination when direct pressure is placed on the pudendal nerve through the rectal wall. If nerve testing is performed, slow conduction of impulses through the nerves may be seen. As is the case with the other pelvic pain syndromes, a careful evaluation must be performed to exclude other, more serious, etiologies for the pain.

HOW IS PUDENDAL NEURALGIA TREATED?

Reassurance from the physician should be provided to alleviate patient fears that a more serious condition is present. Initial management usually consists of a combination of either oral or injected anti-inflammatory agents, physical therapy, and muscle relaxants. A nerve block may provide temporary relief in patients who don’t respond to initial conservative means of treatment. Surgical decompression of entrapped nerves may be considered only in severe, refractory cases.

WHAT IF I CHOOSE TO DO NOTHING ABOUT MY PELVIC FLOOR DYSFUNCTION?

The decision not to undergo treatment for pelvic floor dysfunction is one that should be made only after the patient has undergone a thorough evaluation by a physician who is experienced in evaluating and treating these disorders. Especially when dealing with the pelvic pain syndromes, a thorough evaluation must be performed to exclude a more serious condition, such as rectal cancer or anal cancer. Fortunately, the conditions described above are not life-threatening. Also, most of them are initially managed with non-surgical means, meaning patients are typically more willing to institute a treatment plan.

Should you choose to not undergo treatment, keep in mind that symptoms of pain and discomfort may persist or even progress. In conditions that cause obstructed defection, the inability to effectively evacuate the colon and rectum may lead to long-term damage to the colon, further exacerbating symptoms of constipation.

QUESTIONS FOR YOUR SURGEON:

- What are the options for medical management for pelvic floor dysfunction?

- Do I need a colonoscopy?

- Do I need surgery?

- What are my options for surgery?

- Do I have to go to the operating room for treatment?

- What options do I have for anesthesia with an operative procedure?

- What can I expect after surgery?

- How do you plan to address my pain after surgery?

- What will happen if I don’t want any treatment?

WHAT IS A COLON AND RECTAL SURGEON?

Colon and rectal surgeons are experts in the surgical and non-surgical treatment of diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus. They have completed advanced surgical training in the treatment of these diseases, as well as full general surgical training. They are well versed in the treatment of both benign and malignant diseases of the colon, rectum and anus and are able to perform routine screening examinations and surgically treat conditions, if indicated to do so.

DISCLAIMER

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to ensuring high-quality patient care by advancing the science, prevention and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. These brochures are inclusive but not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on diseases and processes, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. They are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed. It should be recognized that these brochures should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of methods of care reasonably directed to obtain the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all the circumstances

presented by the individual patient.

CITATIONS:

Harford, F.J., Brubaker, L. “Pelvic Floor Disorders.” Chapter 49 in Wolff, B. G., Fleshman, J. W., Beck, D. E., Pemberton, J.H., Wexner, S. D., Eds. The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery. Springer, New York, NY, 2007.

Timmcke, A. “Functional Anorectal Disorders.” Chapter 7 in Beck, D. E., Wexner, S. D., Eds. Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, 2nd Edition. WB Saunders, London, England, 2002.

Green, S. E., Oliver, G. C. “Proctalgia Fugax, Levator Syndrome, and Pelvic Pain.” Chapter 18 in Beck, D. E., Wexner, S. D., Eds. Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, 2nd Edition. WB Saunders, London, England, 2002.

SELECTED READINGS:

http://www.mayoclinic.org/chronic-constipation/

http://my.clevelandclinic.org/disorders/pelvic_disorders/hic_pelvic_floor_dysfunction.aspx