Anal cancer is an abnormal growth of cells in or around the anus or anal canal, the short passage through which bowel movements pass. The most common type of cancer found in this location is believed to be related to a type of viral infection linked to causing other types of cancers as well. Anal cancers are usually treated with radiation and chemotherapy, but surgery alone may be useful for very small or early anal cancers or when other therapy is not an option or unsuccessful in treating the anal cancer. Assessment for cancer spread and close follow up are necessary when treating anal cancer.

This summary is intended for anyone wishing to learn more about anal cancer. After reading this summary, the reader should understand the following:

- The definition of anal cancer and where it develops.

- How frequently anal cancer occurs in the United States and some of the risk factors that put people at increased risk for developing anal cancer.

- How to prevent anal cancer.

- The symptoms that may be associated with anal cancer.

- How to diagnose, stage, and treat anal cancer.

- How to follow patients who have been diagnosed with anal cancer.

DEFINITION OF ANAL CANCER

Cancer describes a set of diseases in which normal cells in the body, lose their ability to control their growth. As cancers – also known as “malignancies” – grow, they may invade the tissues around them (local invasion). They may also spread to other locations in the body via the blood vessels or lymphatic channels where they may implant and grow. This type of cancer spread is also called metastases.

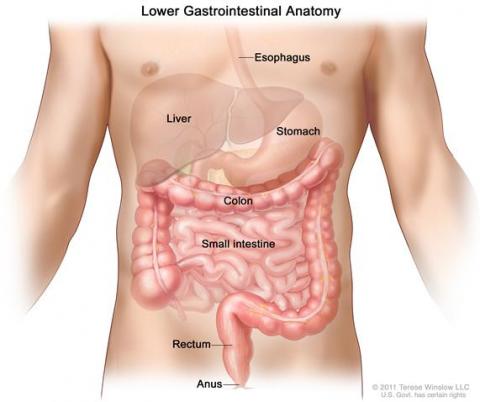

The anus or anal canal is the short passage that is the opening through which stool or feces passes to exit the body at the time of a bowel movement.

(Diagram from NCI)

Photo Courtesy of Robin Noel

Anal cancer arises from the cells around the anal opening or in the anal canal just inside the anal opening. Anal cancer is often a type of cancer called “squamous cell carcinoma” (which includes cancers called basaloid, epidermoid, cloacogenic, or mucoepidermoid – all of which are assessed and treated the same way). Other rare types of cancer may also occur in the anal canal (like gastrointestinal stromal tumors or “GIST” and melanoma to name two), and these require consultation with your physician or surgeon to determine the appropriate evaluation and treatment. Cancer can also develop in the skin in the 5 cm, or approximately 2 inches, just outside the anus. This is called perianal or anal margin cancer and is treated more like a skin cancer.

Cells that are becoming malignant or “premalignant,” but have not invaded deeper into the skin are often referred to as “high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia” or HGAIN (previously referred to by a number of different terms, including "high grade dysplasia," "carcinoma-in-situ," “anal intra-epithelial neoplasia grade III,” “high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion,” or "Bowen's disease"). While this condition is likely a precursor to anal cancer, this is not anal cancer and is treated differently than anal cancer. Your physician or colon and rectal surgeon can help clarify the differences. The risk of these types of premalignant cells turning into cancer is unknown, but is thought to be low, especially in patients with a normal immune system.

ANAL CANCER RATES IN THE U.S.

Anal cancer is fairly uncommon, accounting for about 1-2% of all cancers affecting the intestinal tract. Approximately one in 600 men and women will get anal cancer in their lifetime (compared to 1 in 20 men and women who will develop colon and rectal cancer in their lifetime). Almost 6,000 new cases of anal cancer are now diagnosed each year in the U.S., about 2/3rds of the cases in women. Approximately 800 people will die of the disease each year.

RISK FACTORS FOR ANAL CANCER

A risk factor is something that increases a person's chance of getting a disease. Anal cancer is commonly associated with infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted disease. There are a number of different types of HPV, some more likely to be associated with development of cancer than others. The types of HPV associated with development of cancer usually lead to long-standing and subclinical infection (one that does not show outside evidence of the HPV infection or symptoms/warts) of the tissues in and around the anus as well as in other areas. These types of HPV are associated with the premalignant changes that were described above (high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia or HGAIN). These types of HPV are also associated with an increased risk of cervical, vulvar, and vaginal cancer in women, penile cancer in men, as well as with some head and neck cancers in men and women. Having a squamous cell cancer of the genitals, especially cervical or vulvar cancer (or even pre-cancer of the cervix or vulva), can put people at increased risk for anal cancer – likely from the association with the cancer-causing types of HPV infection.

Interestingly, patients with anal cancer do not appear to be at increased risk for colon and rectal cancer or other cancers in the abdominal organs. It should be noted that not all anal cancers are associated with HPV infection. Some develop without a clear reason.

Additional risk factors for anal cancer include:

- Age - While most cases of anal cancer develop in people over age 55, over 1/3rd of cases occur in patients younger than that. In the United States between 2004 and 2008, the numbers of anal cancers diagnosed by age: 0.0% were diagnosed under age 20; 1.1% between 20 and 34; 9.4% between 35 and 44; 24.7% between 45 and 54; 25.0% between 55 and 64; 18.0% between 65 and 74; 15.2% between 75 and 84; and 6.6% 85+ years of age. As noted above, the incidence of anal cancer in younger men, likely related to HIV (human immunodeficiency virus, the virus that leads to AIDS) infection, has been increasing in some parts of the world.

- Anal sex – People participating in anal sex, both men and women, are at increased risk.

- Sexually transmitted diseases – Patients with multiple sex partners are at higher risk of getting sexually transmitted diseases like HPV and HIV and are, therefore, at increased risk of developing anal cancer.

- Smoking - Harmful chemicals from smoking increases the risk of most cancers, including anal cancer.

- Immunosuppression - People with weakened immune systems, such as transplant patients taking drugs to suppress their immune systems and patients with HIV infection, are at higher risk.

- Chronic local inflammation - People with long-standing anal fistulas or open wounds in the anal area are at a slightly higher risk of developing cancer in the area of the inflammation.

- Pelvic radiation - People with previous pelvic radiation therapy for rectal, prostate, bladder or cervical cancer are at increased risk.

PREVENTING ANAL CANCER

Few cancers can be totally prevented, but the risk of developing anal cancer may be decreased significantly by avoiding the risk factors listed above and by getting regular checkups. Smoking cessation lowers the risk of many types of cancer, including anal cancer. Avoiding anal sex and infection with HPV and HIV can reduce the risk of developing anal cancer. Using condoms whenever having any kind of intercourse may reduce, but not eliminate, the risk of HPV infection. Condoms do not completely prevent transmission of HPV because the virus is spread by skin-to-skin contact and can live in areas not covered by a condom.

Vaccines originally used in clinical trials against the HPV types that have been associated with cervical cancer have also been shown to decrease the risk of developing HGAIN and anal cancer (in men and women), especially in those patients at higher risk (see the risk factors listed above). These vaccines are most effective in people who have not previously been sexually active or have not yet been infected with HPV. The best types of HPV vaccines, how often they need to be given, and who should receive the vaccines remains a matter of discussion.

People who are at increased risk for anal cancer based on the risk factors listed above should talk to their doctors about consideration for anal cancer screening, although this has not been clearly shown to improve outcomes in all patients. This screening can include anal cytology (study of anal cells under a microscope after using a swab on the anal tissues), also known as Pap tests (much like the Pap tests women undergo for cervical cancer screening) as well as use of specialized small, lighted scopes of the anus with high magnification (“high resolution anoscopy” or HRA) that can be used in the clinic or the operating room to assess for premalignant or malignant changes in the anus.

Early identification and treatment of premalignant lesions in the anus may prevent the development of anal cancer. It is unclear how successful these screening tests, and any subsequent treatments, are at preventing cancers or saving lives from the prevention of anal cancer, but this likelihood is thought to be very similar to the improvements found with the use of cervical cancer screening in women using the pelvic exam Pap test. It is unclear how often the anal Pap tests or HRA should be done to successfully identify and prevent anal cancer.

If premalignant changes of the anus or HGAIN are identified, they can be treated through a number of methods to hopefully prevent them from developing into anal cancer, although not all of these changes will actually develop into cancer (the rate of cancer developing into HGAIN is thought to be less than 10% in people with a normal immune system but may be as high as 50% in patients with HIV). Treatment methods include excision (cutting out the abnormal tissue), using electrocautery (focused application of electricity), laser or infrared treatments, phototherapy treatments, radiation treatments, chemotherapy creams (5-fluorouracil or 5-FU), or medications (for example, Imiquimod).

None of these treatments has been studied extensively; none of them is effective 100% of the time; all of them have potential side effects; and all of them require long-term follow-up to confirm success of the treatment. It is best to consult with your physician or colon and rectal surgeon before considering these treatments for premalignant changes of the anus. Remember, these treatments for premalignant changes or HGAIN differ from those for anal cancer (which are described below).

ANAL CANCER SYMPTOMS

While up to 20% of patients with anal cancers may not have any symptoms, many cases of anal cancer can be found early because they form in a part of the digestive tract the doctor can reach and see easily. Unfortunately, sometimes symptoms don’t become evident until the cancer has grown or spread, so it is important to be aware of the symptoms associated with anal cancer, so the cancer may be caught early and without delay. Anal cancers often cause symptoms such as:

- Bleeding from the rectum or anus

- The feeling of a lump or mass at the anal opening

- Persistent or recurring pain in the anal area

- Persistent or recurrent itching

- Change in bowel habits (having more or fewer bowel movements) or increased straining during a bowel movement

- Narrowing of the stools

- Discharge or drainage (mucous or pus) from the anus

- Swollen lymph nodes (glands) or pain in the anal or groin areas

These symptoms can also be caused by less serious conditions such as hemorrhoids, but you should never assume this. More than 50% of anal cancers have a delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis because of the symptoms being mistaken for some other problem (or because the cancer did not have any symptoms). If you have any of the symptoms listed above, see your doctor or colon and rectal surgeon.

DIAGNOSING ANAL CANCER

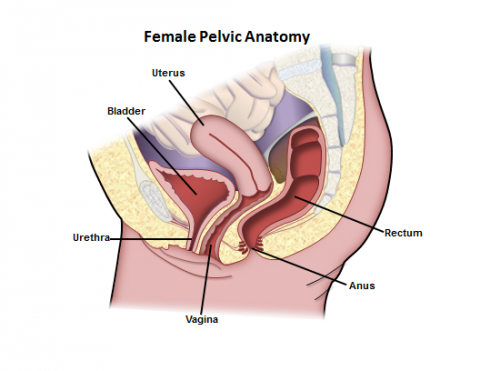

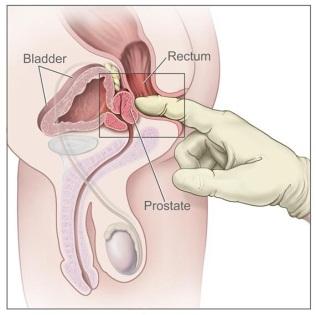

Anal cancer is usually found on examination of the anal canal because of the presence of symptoms like those listed above. It can also be found on routine yearly physical exams by a physician (rectal exam for prostate check or at the time of a pelvic exam in women), on screening tests such as those recommended for preventing or diagnosing colorectal cancer (for example: yearly stool blood tests or a lighted scope exam of the colon and rectum, also known as “colonoscopy”), or even at the time of other anal surgery (such as removal of a hemorrhoid). There are no blood tests to diagnose anal cancer at this time.

Anal cancer is usually found on examination of the anal canal because of the presence of symptoms like those listed above. It can also be found on routine yearly physical exams by a physician (rectal exam for prostate check or at the time of a pelvic exam in women), on screening tests such as those recommended for preventing or diagnosing colorectal cancer (for example: yearly stool blood tests or a lighted scope exam of the colon and rectum, also known as “colonoscopy”), or even at the time of other anal surgery (such as removal of a hemorrhoid). There are no blood tests to diagnose anal cancer at this time.

Photo Courtesy of the NCI

Once there is concern that there may be an abnormal mass in the anus, other tests may be performed to try to diagnose what the mass is.

Anoscopy, or exam of the anal canal with a small, lighted scope, may be performed to visualize any abnormal findings. If an abnormal area is confirmed, a biopsy may be performed to determine the exact diagnosis. This biopsy may be performed in the clinic with the help of a local anesthetic or may be performed in the operating room with anesthesia. If the diagnosis of anal cancer is confirmed, additional tests to determine the extent of the cancer may be recommended. These tests help to stage the cancer in the anus and, thus, help the physician determine a prognosis.

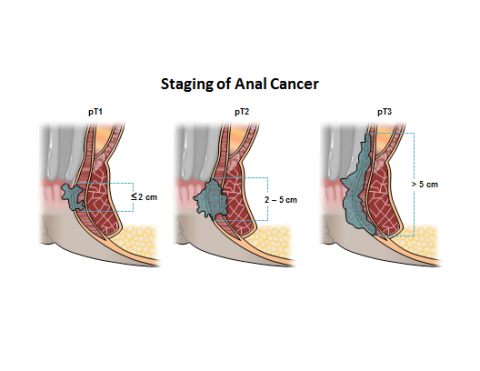

STAGING ANAL CANCER

The stage of a cancer is how advanced the cancer is both in terms of local growth (size of the tumor and whether it has grown into other important structures) and distant spread (“metastasis” or spread into lymph nodes or other structures in the body). Once the cancer is diagnosed, the physician may perform a number of tests to determine the stage of the cancer. Staging helps determine the likelihood that a person may survive the cancer and helps to determine what treatments should be recommended. When anal cancer spreads, it tends to spread to groin lymph nodes or lymph nodes in the abdomen or to other organs like the liver, lungs, and bones. In approximately 15%-30% of patients diagnosed with anal cancer, it will already have spread to the lymph nodes, and in 10-17% it will have spread to other organs.

Courtesy of Robin Noel

The cancer is first staged by physical exam when the doctor examines the anal canal to assess the size of the tumor and where it is growing. They also check to see if they can feel any abnormally large lymph nodes in the groins or elsewhere around the body, and may even use a small needle to biopsy any abnormal nodes (called an “FNA” or fine needle aspiration). A pelvic exam should be performed in all women with anal cancer due to the association with cervical and vaginal cancers. Colonoscopy is recommended for patients with anal cancers who have not yet had one but should have one based on their age or other risk factors for colon and rectal cancer, as determined by their doctor.

Another test may include an ultrasound of the anus (endorectal or endoanal ultrasound) or MRI to assess the cancer’s size, growth into other structures, and whether the nodes around it look enlarged. X-ray tests like a chest x-ray and/or CT scans of the pelvis, abdomen, and/or chest (and/or head if there are concerning symptoms) may be used to look for cancer spread elsewhere in the body. Finally, some patients may undergo a PET scan to look for cancer spread in the body, especially if there are unclear areas of concern on the CT.

TREATING ANAL CANCER

Treatment for most cases of anal cancer is very effective in curing the cancer. There are 3 types of treatment used for anal cancer:

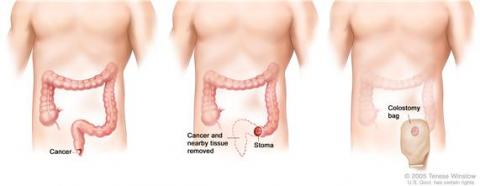

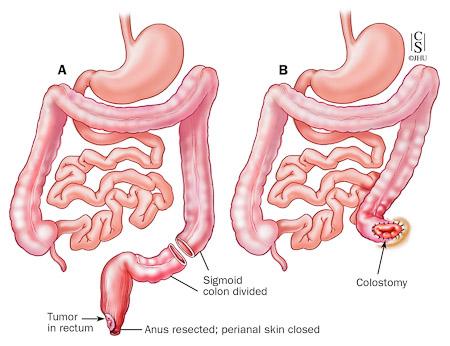

- Surgery: This is when an operation is performed to remove the cancer. Occasionally a very small or early tumor may be removed surgically (“local excision”) without the need for further treatment and with minimal damage to the anal sphincter muscles that are important for bowel control. Sometimes more major surgery to remove the anal cancer is needed, and this may require removal of the anus and rectum and the muscles that are necessary for bowel control, with creation of a permanent colostomy (where the large bowel or colon is brought out to the skin on the belly wall and a bag is then attached with adhesive to the skin to collect the fecal matter).

Photo Courtesy of the NCI

(http://www.cancer.gov/Common/PopUps/popImage.aspx?imageName=/images/cdr/live/CDR415506-750.jpg&caption=Colon cancer surgery with colostomy.)

Part of the colon containing the cancer and nearby healthy tissue is removed, a stoma is created, and a colostomy bag is attached to the stoma.

This is called an abdominoperineal resection or APR, and it used to be the main treatment for anal cancer until the 1970’s when radiation and chemotherapy were found to be successful in treating it. The operation is still used when other treatments fail and the cancer persists (still present locally in the anus within 6 months of completing treatments) or recurs (cancer develops again locally in the anus more than 6 months after having appeared to have been successfully treated), or when patients are not a candidate for other treatment options.

- Complication risks after major surgery are higher, especially problems with incisional healing and infection in up to 80% of patients, after they have had their anal cancer treated with chemotherapy and radiation. While quality of life may be adversely affected by having a colostomy, many patients live normal lives, maintain an active lifestyle, and work while having a colostomy. Surgery can sometimes also be used to remove areas of anal cancer spread, including in groin lymph nodes and other organs, but the success of this type of surgery in curing anal cancer is not as good. Not all patients are candidates for undergoing an operation, especially if other health conditions make surgery unsafe.

- Radiation Therapy: This is when high-dose x-rays are used to kill the cancer cells. Anal cancer is a type of cancer that is very sensitive to radiation, which means it responds well to this type of treatment (especially when chemotherapy is used in addition to the radiation). Usually the cancer is treated as well as the groin areas to try to treat any possible cancer cells that may have spread to the lymph nodes in that region. Complications from radiation occur in up to 40-60% of patients and may include skin damage, narrowing of the anal canal from scarring, anal or rectal ulcers, diarrhea, urgency to have bowel movements or even incontinence (inability to control the bowels), bladder inflammation, or small bowel blockages from radiation damage. There may also be risks of developing other types of cancers secondary to the radiation therapy, but the level of these risks in not known. Any of the radiation complications can occur in both the short- and long-term after undergoing treatments. Some newer types of radiation therapy (for example, intensity-modulated radiation therapy or IMRT) may be considered to try to decrease radiation side effects.

- Chemotherapy: This is when medications are given, usually intravenously (directly into a vein) in the case of anal cancer, to kill cancer cells. These treatments were found to provide an added benefit to the use of radiation and improve the likelihood of avoiding the need for surgery for anal cancer. Drugs that are commonly used for anal cancer include 5-fluorouracil or 5-FU, mitomycin C, and cisplatin. These medications have some common side effects that include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hair loss, decrease of the bone marrow to produce immune and blood cells, lung inflammation or lung scarring, or changes in nerve function of the hands and feet. Even death can occur from the use of these medications, but this is rare (less than 5% risk) and usually occurs in patients with other health conditions prior to treatment.

Combination therapy including radiation and chemotherapy is now considered the standard treatment for most anal cancers. Although this combination may have higher risks of side effects, it has shown the best long-term survival rate from anal cancer, with up to 70-90% of patients still alive and cancer free at 5 years after completing treatments. If the cancer recurs or persists, however, surgery such as an APR can still potentially cure the cancer but not as successfully (studies show anywhere from 24% to 69% of patients are cancer-free and alive at 5 years from surgery after failing chemotherapy and radiation). The majority of patients with anal cancer are able to avoid the need for a permanent colostomy, however.

Another option for anal cancer is not to undergo any treatment. If no treatment is given for anal cancer, the cancer will continue to grow and likely spread. If the cancer grows locally, it may cause bowel blockage, abnormal connections (“fistula”) between the anus and other organs (for example, the vagina or bladder), pain as it grows into nerves or other structures, bleeding, bowel incontinence, or other symptoms. Once the cancer has spread, most patients will not live longer than 1-2 years without treatment. Pain medications, palliative surgical procedures, and supportive care can often help to keep patients comfortable from the effects of advanced anal cancer.

FOLLOW-UP AFTER TREATING ANAL CANCER

Follow-up care to assess the results of treatment and to check for recurrence is very important. Most anal cancers are cured with combination therapy and/or surgery as noted above. In addition, some cancers that recur despite treatment may be successfully treated with surgery if they are caught early, so patients are encouraged to report any concerning symptoms to their treating physicians right away. A careful examination of the anus with finger exam and (if needed) anoscopy as well as physical exam by an experienced physician or colon and rectal surgeon at regular intervals is the most important method of follow-up. These exams are recommended every 3-6 months for the first 2 years after the diagnosis, then every 6-12 months for up to 5 years, and then yearly thereafter. Additional studies may also be recommended including endorectal ultrasounds, CT scans, MRI scans, chest x-rays and/or PET scans, especially if there is concern for cancer recurrence.

CONCLUSION

Anal cancers are unusual tumors arising from the skin or lining of the anal canal. As with most cancers, early detection and appropriate treatment is associated with a high likelihood of surviving the cancer. Most tumors are well-treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiation. In the circumstance where the cancer recurs despite treatment, the cancer may be treated successfully with surgery. It is recommended to follow screening examinations for anal and colorectal cancer and consult your doctor or colon and rectal surgeon early when any concerning symptoms occur.

QUESTIONS FOR YOUR COLON AND RECATL SURGEON IF YOU ARE DIAGNOSED WITH ANAL CANCER:

- Has the diagnosis been confirmed by biopsy?

- What are my risk factors that may have contributed to my getting anal cancer?

- What staging studies do I need for my cancer?

- Do I need a colonoscopy?

- Do I need a pelvic exam? (for women)

- What treatments or referrals will I need?

- Do I need surgery, and if so, will I need a colostomy?

- What should I expect in terms of overall recovery and time in the hospital?

- What are the short- and long-term risks related to surgery?

- How do you plan to address my pain after surgery?

- What is your experience and outcomes with performing surgery for anal cancer?

- What will happen if I don’t want any treatment for my anal cancer?

- Are there other treatments or trials available that I might be a candidate for?

- How often do I need follow up and what follow up tests will be done?

WHAT IS A COLON AND RECTAL SURGEON?

Colon and rectal surgeons are experts in the surgical and non-surgical treatment of diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. They have completed advanced surgical training in the treatment of these diseases as well as full general surgical training. Board-certified colon and rectal surgeons complete residencies in general surgery and colon and rectal surgery, and pass intensive examinations conducted by the American Board of Surgery and the American Board of Colon and Rectal Surgery. They are well-versed in the treatment of both benign and malignant diseases of the colon, rectum and anus and are able to perform routine screening examinations and surgically treat conditions if indicated to do so.

DISCLAIMER

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to ensuring high-quality patient care by advancing the science, prevention and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. These brochures are inclusive but not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on diseases and processes, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. They are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed. It should be recognized that these brochures should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of methods of care reasonably directed to obtain the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

CITATIONS AND SELECTED READINGS

Welton, M. L. and Raju, N. Chapter 20, “Anal Cancer” Chapter in Beck, D. E., Roberts, P. L., Saclarides, T. J., Senagore, A. J., Stamos, M. J., Wexner, S. D., Eds. ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery, 2nd Edition. Springer, New York, NY; 2011.

ASCRS website, 2008 Core Subjects; Dunn, KB “Anal Tumors”

Steele, S. R., Varma, M. G., Melton, G. B., Ross, H. M., Rafferty, J. F., Buie, W. D., Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice Parameters for Anal Squamous Neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55(7):735-49.

For the latest information about anal cancer statistics in the United States, see the National Institutes of Health Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) website: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/anus.html

For the latest information about anal cancer from the American Cancer Society, please see: http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/AnalCancer/DetailedGuide/index.htm